“Pee is for Politics”

Date: Aug 2016

Location: Råhuset, Copenhagen

Collaborators: Enrique Molins, Frederikke Bencke and Susanne Bartholdsson

Imagine a warm summer evening. You meet up with your friends, and after a while, your bladder is full and you have to pee. You go find the nearest public urinal, or a tree. Relatively straightforward manoeuvre. If you are male. For the female population of the city, the need to access public toilets can quickly become an urban nightmare as the city experience an urgent lack of public toilets for women. Peeing in public is usually a practice which is socially acceptable for men, and for women this idea of squatting in public is intimidating and mostly not an option. Often women, who are not up for the task of baring it all by peeing on the street, because of lack of public toilet facilities have to negotiate access to toilets from cafés and restaurants – something which is often only possible in exchange for payment. We find this lack of facilities deeply problematic, and argue that the practice of sexist urban planning is not a sustainable way of imagining an inclusive cityscape. Copenhagen often position itself as being a city of social values related to multiplicity and inclusivity. If a city is to be an inclusive, safety and urban facilities should be available to everyone inhabiting it, and the exclusion arising from a preferential gendered urban planning disrupts this project. To imagine the city of the future, we challenge the idea of a cityscape privileging the male population, and encourage planners and stakeholders to do the same. In extension of this, we have produced a potential solution to the issue, and provided a vision for a prototype.

Below is a map of Kødbyen comparing the number of places where men, women and differently-abled people can pee.

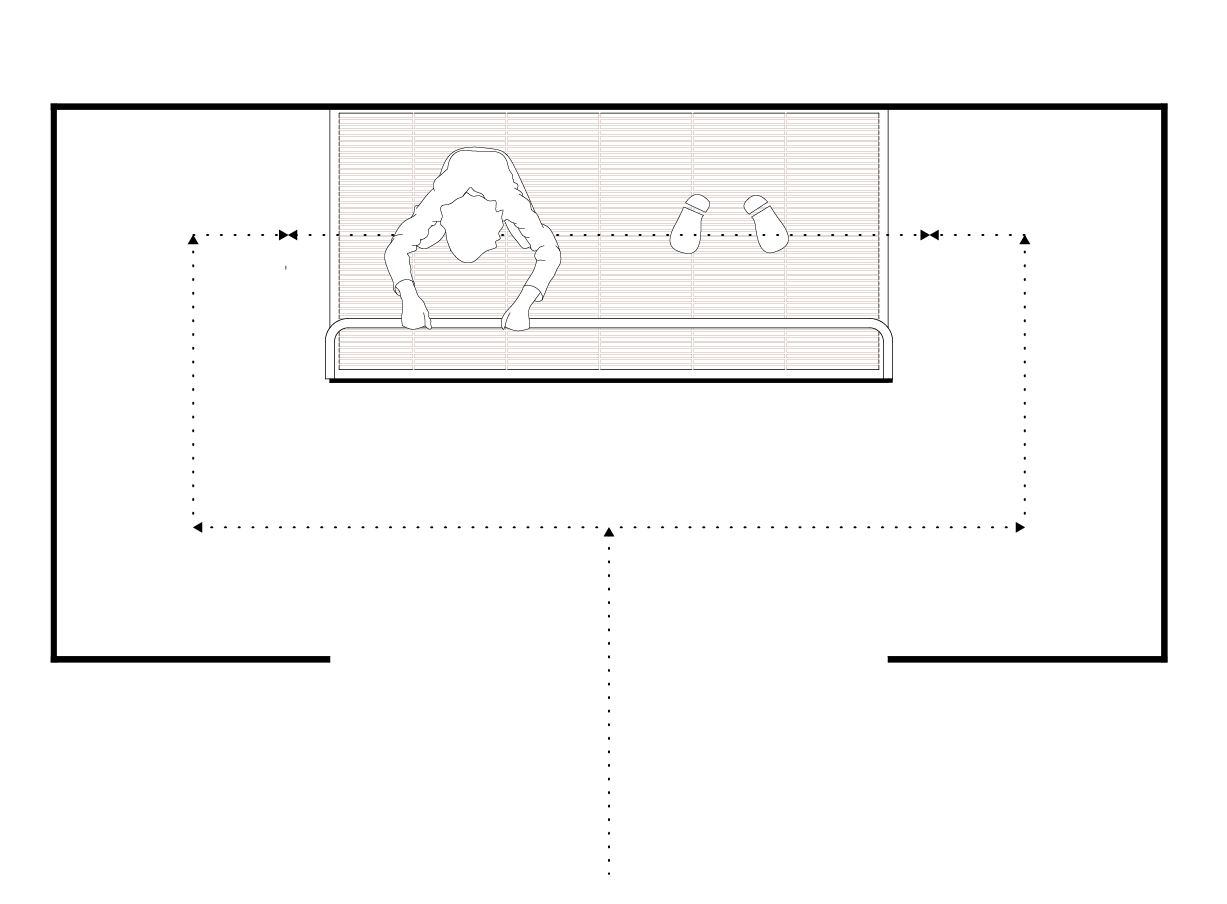

This was our basic prototype for a women’s urinal. A shielded space with 2 accesses, where women could squat down and pee onto a grate and walk out. A bar would be placed for support while squatting and to help yourself up. A hanger would be place behind to hold bags and other accessories. A look-out strip would be opened at the height of 150cm-180cm and closed with a reflective glass panel so women inside can look out and passers-by cannot see inwards.

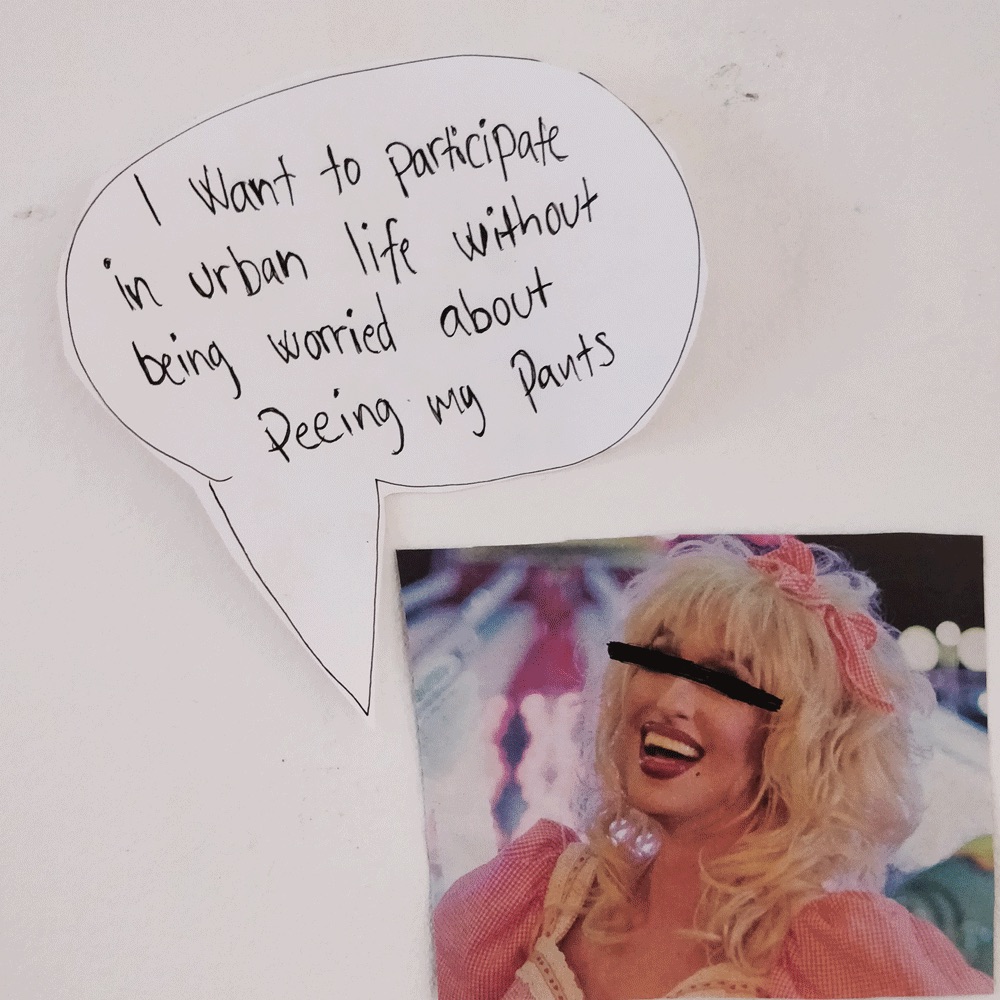

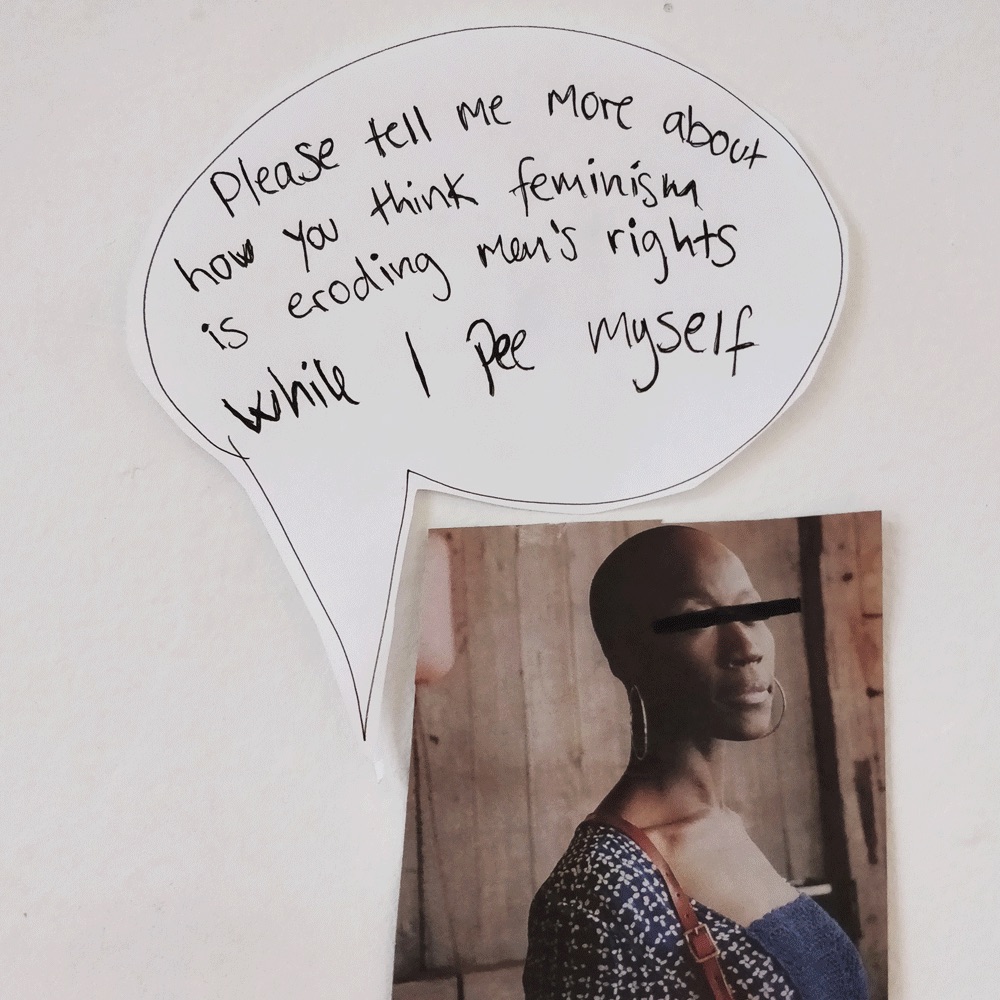

It was important for us to bring this issue to people’s attention, both women who were conditioned to accept gendered urbanism, challenging us to find a place to pee in a timely manner and men who may not be aware of the

privilege they receive through common practices in urbanism.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()